Once upon a time, in a parish far far away, a young man in his teens had the task on Friday mornings of leading the recitation of The Litany, a form of petitionary prayer, using The Book of Common Prayer. He had grown up using the book from his early days, indeed His mother had given him his first copy of the said book for Christmass in the early 1960s. He was thus familiar with the cadences and forms of the Book of Common Prayer, and was very much at ease in its use.

One particular Friday as the Litany progressed he was especially struck by the words of one of the petitions in the Book: “By the mystery of thy holy Incarnation, by thy holy Nativity and Circumcision, By Thy Baptism, Fasting, and Temptation, Good Lord deliver us.”

The book’s composer had obviously intended that its contents, of which that petition was representative, should not only be a form of prayers to be used by the Church of England, which indeed it still is (including us here down under) like some sort of prayer manual, a device to provide a pattern of worship; but that there should be much more to it than that.

To cut a long story short the intent of its original author, mainly Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556), although he drew on many other sources, was that a mystical idea which we call Incarnational Theology, should be found at the very heart of how the creature we know as the Church of England, would worship the Holy and Triune God. That church, of which we are a part, although having a few of the benefits, and not to mention some of the great faults of the english reformation, would no less still share in the ancient faith and emphasis passed on from the Eastern and Western Churches.

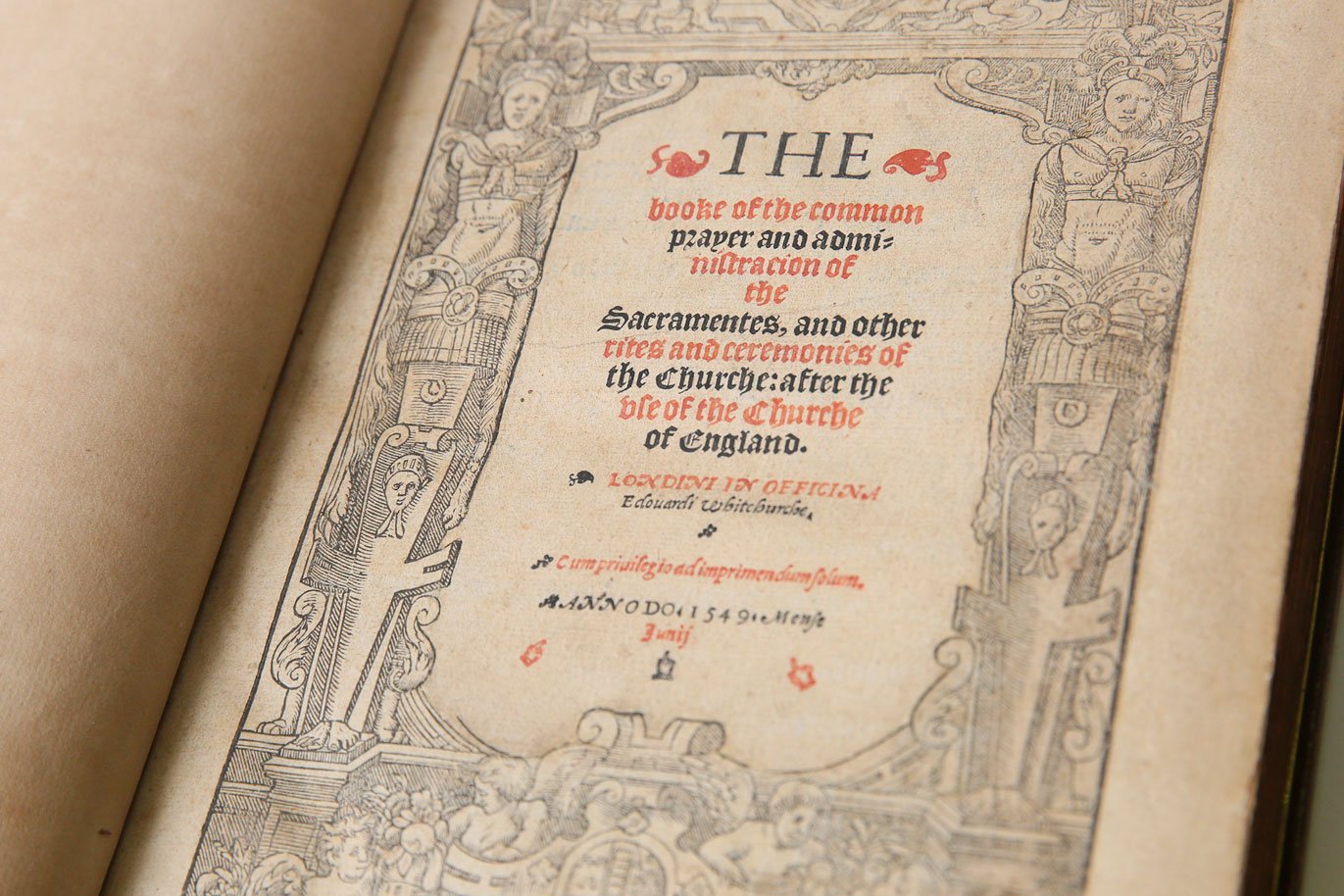

The book of course has itself had a varied and interesting history. Its first edition was approved in the year 1549. A revision, less well crafted, was published in 1552, with a further, better one, being authorised in 1559 during the reign of Elizabeth I. Those of you who have seen the film in which Cate Blanchett played Queen Elizabeth will remember the scene in which the usage of the book as part of the Act of Uniformity was debated in parliament. If you have not, it is well worth searching out. The book had some revision to it again in 1604.

Sadly, for a little while when the monarchy and Church of England were under attack after the period of the English Civil Wars (roughly 1642-1651), and with the martyrdom of King Charles I and the suppression of the Church of England, the book was not used, except by those Anglican Clergy who kept faith and were effectively living under internal exile.

A yet further revision was approved in 1662 after Charles II was restored to the Throne and the Church of England, not to mention the whole country, was set free of its oppression from puritan/commonwealth forces. It is that book which is still in effect even today.

An attempted revision was undertaken early in the 20th century (referred to as the Book of Common Prayer as proposed in 1928), which was regrettably rejected by the British Parliament (for reasons too complicated to go into here). Many bishops though still authorised its use anyway, as they did not believe that Parliament was competent to act regarding such a matter. (They were right)

Since then each province of the Anglican Communion has issued modern prayer books, all of which are supposed to follow the pattern and doctrine of the Book of Common Prayer. Here in Australia we did so in 1978 and 1995. The USA and South Africa did so in 1979.

So, why do we have prayer books, missals, overhead projectors, whatever? Why do we organise the way we worship at all? Surely we could just get by ad hoc.

The answer in part is because worship does need to be organised. St Paul recognised the need for some conformity in worship when he took the Corinthians to task for making a mess of it in one of his letters to them.

More than that though, the Church needs to frame its worship in relation to how God has made himself known to us, and how important doctrines relating to that are made understandable and memorable to its members.

A prayer book is more than just a business paper arranged in point form with paragraphs and subparagraphs, debated clause by clause. It is, or it should be, an expression of doctrines and precepts that have to do with how God loves us and grants us his mercy and makes himself present amongst us, whilst we for our part respond faithfully to him.

The young man progressed as he grew older, and has used other forms of liturgy, some very good, some appallingly bad. Still he has a respect for the book that has sustained this part of the Church Catholic for so many centuries and whose cadences are so well known. Hopefully it will continue to be useful and encouraging to others as well.